Sensory Orchestration – Project Highlights

We recently drafted our final project report and thought this would be a perfect opportunity to share some of the highlights of the ‘Sensory Orchestration’ project.

Over the course of the project, we have explored multimodality and the role of the senses across makerspaces, digital imagery and photography and extended reality technologies (mixed reality, virtual reality, and augmented reality).

Makerspaces

In the first phase of our research, we investigated the sense of touch, soundscapes and acoustics in Makerspaces. Makerspaces are community-based collaborative workspaces, often located in community settings, such as libraries and educational locations, that provide people with access to tools and other materials for creating, inventing, and learning. Typically, these tools include various technologies such as 3D printers, laser cutters, electronics equipment, and even tools for wood working and other industrial design activities (makerspaces.com).

We worked collaboratively with U.S. and Australian industry and research colleagues in three makerspaces sites. We wanted to explore the ways in which students incorporated touch into their designs and how they orchestrated this tactile element alongside other sensory resources, including soundscapes and acoustics. Based on these observations, Dr Lesley Friend and Professor Kathy Mills developed a unique ‘touch typology’. This noted the concepts of creative touch, auxiliary touch, and evocative touch, interwoven with orchestrated and transformative touch. More about this unique typology can be found in Friend & Mills’ (2021) open access article, Towards a typology of touch in multisensory makerspaces. Figure 1 shows an example of a student’s e-sculpture, comprising of sculpted clay and embedded with electronics programmed with an Arduino™ Kit. These e-sculptures were created in one of our makerspace workshops.

Figure 1: An example of a student e-sculpture, programmed to give the face a ‘winking eye’.

Interwoven with our research into makerspaces, we also worked with theatre educator and performer, Nathan Schulz, or The Drama Merchant. This collaboration with The Drama Merchant provided the opportunity to explore the creation of soundscapes using foley space and equipment. As a result, students produced immersive audio environments, and examples include a boat in a storm and a steam train. Examples can be heard at this Soundcloud link.

The senses and Extended Technologies (MR, VR and AR)

Extended reality technologies have become one of the fastest growing technologies for educational use (Eldequaddem, 2019), although research has been limited into the use of these technologies for literacy and language learning (Ok et al. 2021). Extended reality technologies encompass virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR). VR provides a wholly immersive digital experience, and typically involves the use of head mounted display (HMD). AR overlays digital or rather virtual content on real world, and MR interactively merges the virtual with the real world. Given such growth, it provided an excellent opportunity to investigate these technologies in literacy and language contexts and to explore the range of distinctive potentials they offer (Mills, 2022). Such unique potentials include the role of the senses in literacy and language learning as they pertain to the interactive and immersive digital environments.

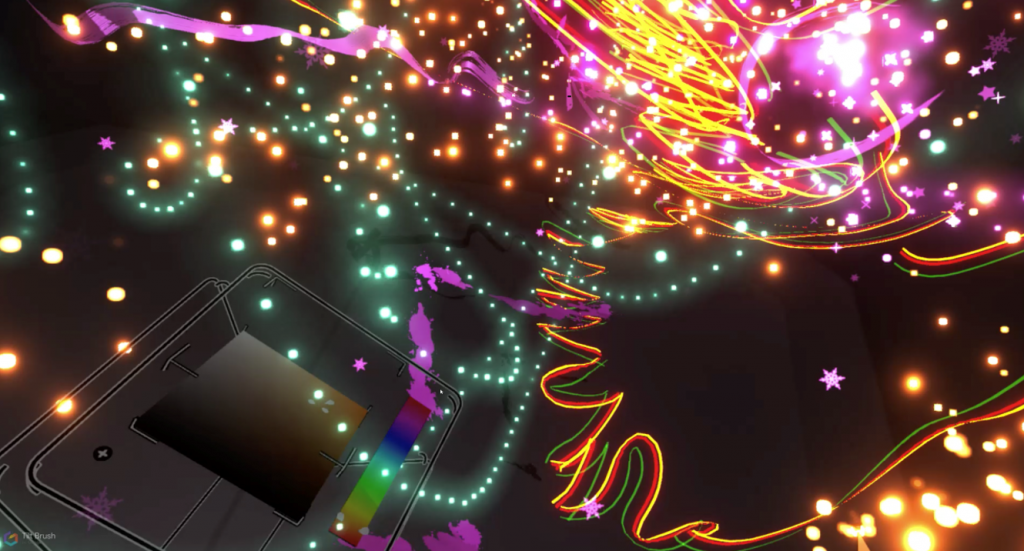

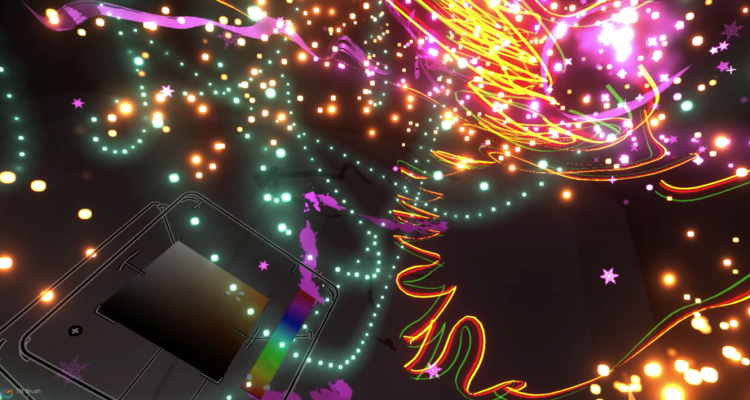

Data collection and analysis in the extended realities component of the project included multimodal and digital data and investigated the learning experiences of upper primary students. From this portion of our research, we explored two processes with digital media making in immersive VR environments: transmediation and embodiment. We were keen to see what the opportunities and limitations of virtual reality was for translating ideas from conventional modes of drawing and writing to the immersive mode of virtual painting. For this research we employed the Google TiltBrush™ in the retelling of Greek myths, and how virtual paining contributes to embodied multimodal representation. For further details about this work, check out our open access articles, Immersive virtual reality (VR) for digital media making: Transmediation is key (Mills & Brown, 2022) and Virtual Reality and Embodiment in Multimodal Meaning Making (Mills, Scholes & Brown, 2022). The example in Figure 2 illustrates how students used the Google TiltBrush™ to create virtual paintings that illustrate mood.

Figure 2: An example of a student illustrating the emotion ‘happy’ in the virtual painting component of the study.

In addition to this, we studied how students could use virtual reality to connect new knowledge from past experiences. Drawing from the concepts of multiliteracies pedagogy, the team aimed to understand how upper primary students (aged 10-12) engaged with VR to create intricate three-dimensional Roman vessels. This immersive process involved combining various modes of meaning and cultural cues, offering a novel way for students to connect with history. We look forward to sharing a forthcoming article about this soon. An example of these virtual vessels can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3: An example of a student created Roman vessel using virtual reality technology.

Following this work, Kathy Mills and Alinta Brown (2023, p.3) explored two key research questions: “(i) How can smart glasses support students’ multimodal composition in the classroom? (ii) What multimodal resources are available to students wearing smart glasses to compose narratives?”.

In this study, we explored the use of smart glasses (mixed reality) for multimodal composition, aiming to compare students’ prior narrative creation experiences. We analysed transmedia stories crafted with smart glasses, alongside other school-based story-making activities. The students noted that despite the media shift, storytelling remained central, while highlighting the interactive aspect of the technology. This research viewed students as both learners and creators, offering fresh insights into unconventional story crafting. This prompts consideration of mixed reality’s potential role in haptically-interactive reading, comprehension, and broader story-related aspects beyond the current exploration of these literacy practices. You can read more about this work in Mills’ and Brown’s 2023 open access paper, Smart glasses for 3D multimodal composition.

Most recently we explored the role of augmented reality in the area of reading and comprehension. This was the focus of our earlier blog post Reading with VR and AR (Fieldwork Day 3), and will be further expanded in our upcoming report. Students engaged across the various AR applications, and we used both AR Makr, in which students could transmediate a scene from a story they had written in class, and Merge Cube™ and the Explorer™ app, and provided a tangible and tactile approach to various AR based activities. Figure 4 shows an example of augmented reality and the creation of a space story scene created in AR Makr.

Figure 4: ‘Barry goes to space’. An example of a story scene created in AR Makr

Digital Imagery and Photography

Throughout the project, students participated in diverse digital imagery and photography tasks. In partnership with Mark Williamson of Big Picture Industries, and interwoven with our mixed reality research activities, students explored digital photography to create and manipulate imagery. For instance, they combined DSLR photography with textile-focused visual arts, creatively weaving principles of textiles into their photographs. Figure 5 shows an example of student creativity using images taken on DSLR cameras, that were later edited and refined for understanding image manipulation and composition.

Figure 5: An example of student creativity using images taken on DSLR cameras.

Another workshop encouraged hands-on, out-of-classroom learning, paralleling VR activities and contributing to their augmented reality scene creation. Additionally, students explored perspective by manipulating physical objects to change proportions, comparing them to AR digital overlays that simulated size variations in virtual scenes. This provided engaging and innovative learning experience for the participating students.

We will have more to share with you soon!

References and further reading:

Elmqaddem, N. (2019). Augmented reality and virtual reality in education. Myth or reality?. International journal of emerging technologies in learning, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i03.9289

Friend, L., & Mills, K. A. (2021). Towards a typology of touch in multisensory makerspaces. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(4), 465-482. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1928695

Makerspaces.com (n.d.). What is a makerspace? https://www.makerspaces.com/what-is-a-makerspace/

Mills, K. A. (2022). Potentials and challenges of extended reality technologies for language learning. Anglistik, 33(1), 147-163. https://doi.org/10.33675/ANGL/2022/1/13

Mills, K. A., & Brown, A. (2022). Immersive virtual reality (VR) for digital media making: transmediation is key. Learning, Media and Technology, 47(2), 179-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1952428

Mills, K. A., & Brown, A. (2023). Smart glasses for 3D multimodal composition. Learning, Media and Technology, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2207142

Mills, K. A., Scholes, L., & Brown, A. (2022). Virtual reality and embodiment in multimodal meaning making. Written Communication, 39(3), 335-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/074108832210835

Ok, M. W., Haggerty, N., & Whaley, A. (2021). Effects of video modeling using an augmented reality iPad application on phonics performance of students who struggle with reading. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(2), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2020.1723152